Signals in the Void

What We've Told the Cosmos About Ourselves in Our Messages Sent to Space

We have a history of leaving messages and sending signals that convey our experiences. Oftentimes, we’ve left these for other humans—trail markers and signals to let other people know where we’ve been and how to follow. We’ve sent smoke signals and lit beacons to communicate over distances. We’ve figured out how to use animals to carry messages on our behalf, we’ve developed systems for mail carrying to communicate via written word, and eventually developed the telegraph, the telephone, the instant message, and the Zoom call to communicate digitally across the world.

Sometimes we’ve had to reach out for help through our messages.

As the Titanic was sinking on that tragic night in April of 1912, wireless operators sent CQD and SOS distress calls, and a back and forth among ships across the Atlantic led to the few survivors being saved. When the crew of Apollo 13 realized they had suffered a catastrophic systems failure en route to the Moon, the calm but urgent message—“Houston, we’ve had a problem”—was received by mission control, sparking a heroic effort to return the crew to Earth. And seventeen days after the San José mine collapse in 2010, rescuers retrieved a small note from a borehole probe that translates as “We are well in the shelter, the 33.”

Sometimes we’ve sent our messages out into the ether, not knowing if others might hear us or be able to respond. There are many recorded cases of people sending out the literal message in a bottle: recording a message for a loved one and then tossing it to sea to be found years or decades later. Sadly, some distress calls from sinking ships, people in peril in the wild, and maydays from aircraft suffering terminal failures have gone unanswered or those receiving them may have had limited capability to offer any help.

Our messages at other times have been driven by curiosity, hope, and deep yearning to be known.

In the vast silence of space, that impulse takes on an even more poignant tone. Across the last many decades, we’ve sent crafted artifacts, encoded music and images on physical devices, and fired off signals towards space, hoping that someone—or something—might one day receive them.

(Note: I got a little carried away on this writing, so you might need to open it in a browser to read the full piece)

Monuments to Our Moment: Apollo and Pioneer Plaques

We sometimes have a tendency to want to “leave our mark” to signify to ourselves and others when we feel we’ve accomplished something. We see that in the feeling of significance for some of “planting the flag”, where a nation claims a new shore or new frontier by planting their flag. While there are nationalistic and colonialist overtones to the concept of planting a flag to claim some territory, it doesn’t seem to be a behavior we’re ready to leave behind.

We’ll probably see the first people walking on Mars planting a flag of their own, much as the Apollo astronauts carried US flags to the Moon to be planted.

But more important than those flags, in my opinion, are the plaques that we left behind with each lander.

Attached to the ladders on the lunar landers and then left behind on the Moon, the first (Apollo 11) and the last (Apollo 17) are probably the most significant as they left behind not just names and signatures of astronauts but also had messages.

The Apollo 11 plaque reads:

HERE MEN FROM THE PLANET EARTH FIRST SET FOOT UPON THE MOON JULY 1969, A.D.

WE CAME IN PEACE FOR ALL MANKIND

The Apollo 17 plaque shares the final message:

HERE MAN COMPLETED HIS FIRST EXPLORATIONS OF THE MOON DECEMBER 1972, A.D.

MAY THE SPIRIT OF PEACE IN WHICH WE CAME BE REFLECTED IN THE LIVES OF ALL MANKIND

These plates of metal with etchings in them are less about sending messages to the stars, and more about leaving a mark of the time in human history—signifying to ourselves the importance of our first human explorations of another celestial body. And, honestly, the language is far more inclusive of humanity and less nationalistic than the flags we planted.

But perhaps our first real “postcards” to the stars were the Pioneer plaques. Also etched plates of metal, they were included with the Pioneer 10 and 11 missions, knowing that those spacecraft were destined to travel away from our solar system and out into the void. The Pioneer plaques are the first physical messages sent with the intention of communicating who we are with potential alien intelligences who may find these craft some eons in the future.

The messages on these plaques are rooted in the hope that an alien intelligence may understand some of the same math and science that we do.

I won’t break down the full message here (though it’s super fun to explore in depth what each part of the message describes). But here are some of the basic ideas represented on these plaques:

The top of the plaque shows the hyperfine transition of neutral hydrogen. This is used as a legend for the rest of the figures, so if an alien civilization has conceptualized some of the physics we have, they could use this as a base for measurement for the rest of the images.

The human figures are shown along with the spacecraft itself. The creators had intended for the human figures to appear panracial, but had received criticism that they appear mostly European in ancestry. But on the far right, a scale is used along with binary to give the average height of a human woman (again using the scale from the legend). Of course, this assumed that an alien species would understand sexual dimorphism in our species (they might not have that), but at least it would show what we looked like to them.

The bottom shows a diagram of the planets of our solar system with the distances from the Sun encoded in binary and a graphic representation showing that the spacecraft had been launched from the 3rd planet from the Sun.

And probably the coolest past of the message is the pulsar map, showing our location relative to 14 nearby pulsars in the galaxy. There’s a long line that represents our distance from the galactic center and then polar coordinates encoded in binary showing our location and distance from these pulsars. An alien civilization could potentially read this and know where our solar system is located within the galaxy!

The Golden Recordings Aboard the Voyagers

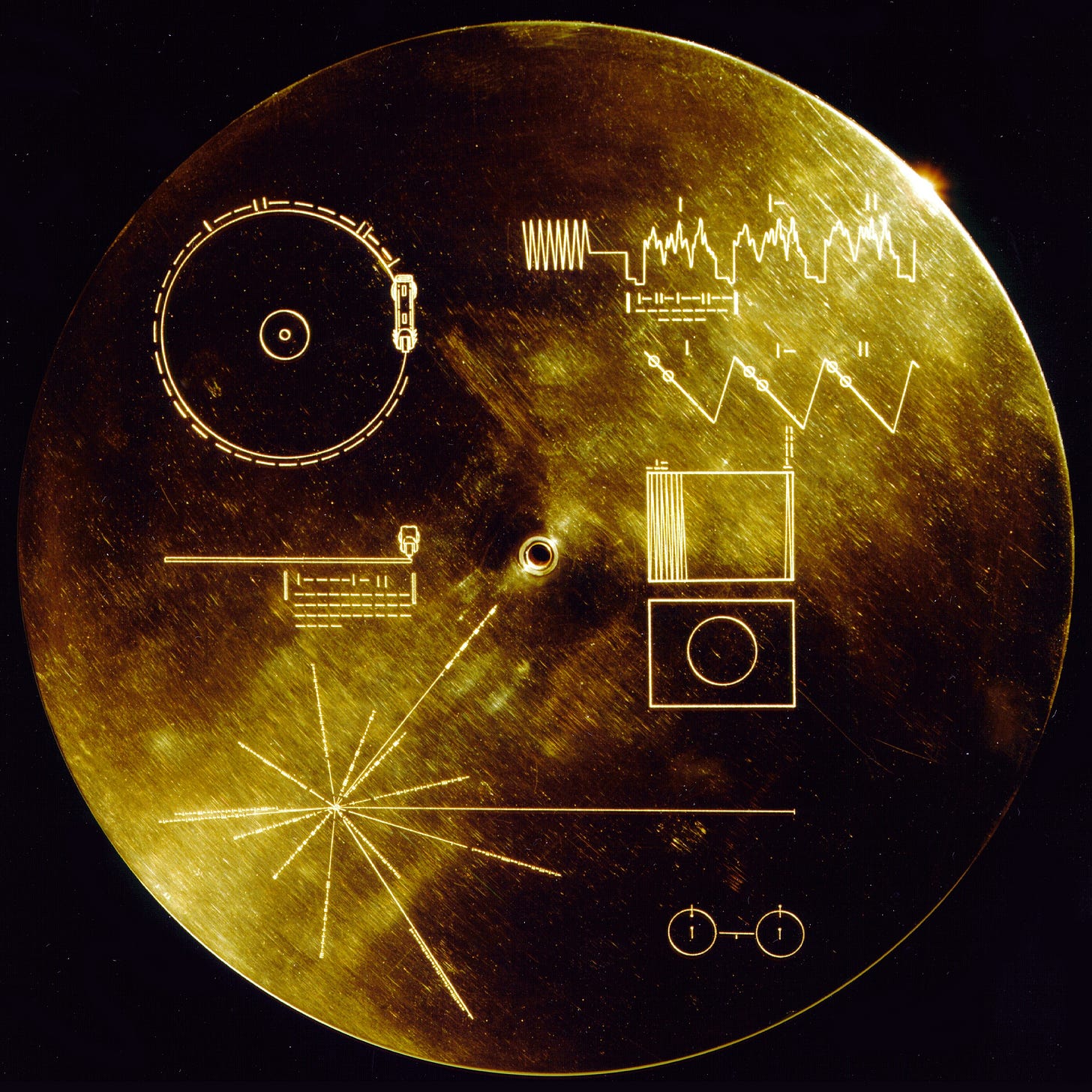

If the Pioneer plaques were our postcards to space, then the Voyager Golden Records are our cosmic mixtapes.

Launched in 1977, these gold-plated copper discs carried greetings in dozens of languages, sounds of Earth, and selections of music—from Bach to Blind Willie Johnson. Curated by a team led by Carl Sagan, the records represented an ambitious attempt to communicate not just facts, but feelings. An alien might learn about our biology and geography—but also our capacity for art, rhythm, and longing.

Due to issues (mostly from a state of prudishness) of having nude figures on the Pioneer plaques, the covers placed over the records did not include images of human beings (imagine, though, if we had put human figures in clothing in the images—what a statement about our silly lack of maturity that would have been). The covers did, though, include messages of math and science and explained how an intelligent species could “play” the records.

The hyperfine transition of neutral hydrogen is again used as a legend and the pulsar map is there as well. But the cover art also includes information on how to spin the record and use an included stylus to transmit the vibrations of the recordings at their intended rate. There’s also a series of diagrams explaining how to extract and view the image data.

The records themselves contain a carefully curated collection of audio and visual material divided into several thematic sections. The first is a series of spoken greetings in 55 languages, including a welcome from then-U.N. Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim. The second section features a range of Earth sounds—the crashing of waves, the call of a humpback whale, laughter, a heartbeat—meant to convey the diversity of our planet's natural and human-made environment. The third section is a musical anthology spanning cultures and centuries, from Bach and Beethoven to Navajo chants and gamelan music from Indonesia. The fourth section includes the 116 analog-encoded images that depict life on Earth—from human anatomy and mathematics to architecture, landscapes, and everyday life.

The very end of the record includes two images that detail a message from then-President Jimmy Carter which read:

This Voyager spacecraft was constructed by the United States of America. We are a community of 240 million human beings among the more than 4 billion who inhabit the planet Earth. We human beings are still divided into nation states, but these states are rapidly becoming a single global civilization.

We cast this message into the cosmos. It is likely to survive a billion years into our future, when our civilization is profoundly altered and the surface of the Earth may be vastly changed. Of the 200 billion stars in the Milky Way galaxy, some--perhaps many--may have inhabited planets and spacefaring civilizations. If one such civilization intercepts Voyager and can understand these recorded contents, here is our message:

This is a present from a small distant world, a token of our sounds, our science, our images, our music, our thoughts, and our feelings. We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours. We hope someday, having solved the problems we face, to join a community of galactic civilizations. This record represents our hope and our determination, and our good will in a vast and awesome universe.

The Golden Records also include a hand etched inscription on the records themselves that say, profoundly: “To the makers of music – all worlds, all times.”

But as if all of this wasn’t enough, perhaps one of the best things about the records (in my opinion) is that they include physical timestamps to record the time when the records were launched.

Each of the record covers includes on their inside surfaces an ultrafine layer of pure Uranium-238. U-238 has a halflife of 4.468 billion years. This means that any sufficiently advanced civilization that could find and play one of the records to learn more about us through our sounds and our images could also use that layer of uranium to figure out how long it had been since the spacecraft was launched. Even if it takes a billion years or more, the U-238 timestamp would let them precisely determine how long the spacecraft had been traveling through the cosmos.

A few years ago (in 2017), Ozma Records used the original masters from the records to rerelease a full digital listing of the contents of the records. You can listen to the entire track listing on the Internet Archive.

If you’re into podcasts, I also highly recommend giving a listen to the episode, The Voyager Golden Record: Humanity’s message to the Cosmos from Twenty Thousand Hertz, which explores the audio contents in more detail, and with commentary from Timothy Ferris and Linda Salzman-Sagan, both of whom took part in the original developments of the records.

The Voyager Golden Records are a testament to our time and place right now in the cosmos. The Voyagers have been traveling for over 47 years, flying away from the Sun at over 30,000 mph. At the exact time I’m writing this, Voyager 1 is over 15 billion miles away and Voyager 2 is almost 13 billion miles away. While we know that we will someday soon lose contact with these spacecraft, the messages they carry will continue traveling away from us for many eons to come.

Arecibo and the Age of Broadcast

As anyone who’s watched Contact knows, our radio and television signals have long been traveling through space. Although, as Seth Shostak of the SETI Institute has pointed out many times, those signals are fairly likely to be so low in signal as to be nearly indecipherable by the time they get to most star systems. Seth likes to point out that the strongest signals we regularly have been sending into space for decades are actually from our military radar bases that are constantly pinging the skies and looking for signs of missile attacks between world powers.

But we also have sent many intentional messages into space.

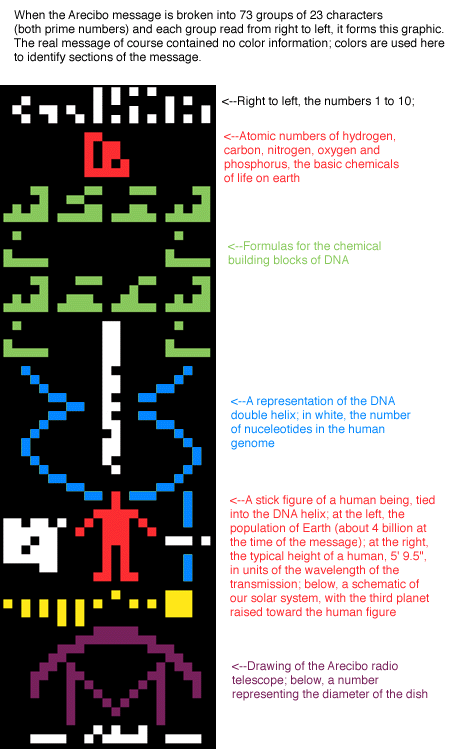

The most famous of them all is the Arecibo Message. Sent in 1974 from the now-lost Arecibo dish, the message was a string of binary code sent in radio toward the M13 star cluster. It will take some 24,000 years for the signal to arrive around those stars, so the message wasn’t really sent with intention of being heard by anyone anytime soon, but the message was an attempt to shows that we could enode a potentially useful message (and that maybe alien civilizations have elected to do the same).

But many people are unaware that we have actually sent many encoded messages into space now.

Various projects from a number of different groups, including METI International (their name stands for Messaging Extraterrestrial Intelligence), have sent voices, music, and other audio selections toward stars in the Milky Way. These include projects like Cosmic Call, Teen-Age Message, and others. Each message, in its own way, tries to answer a basic question: if we met someone across the stars, what would we want them to know?

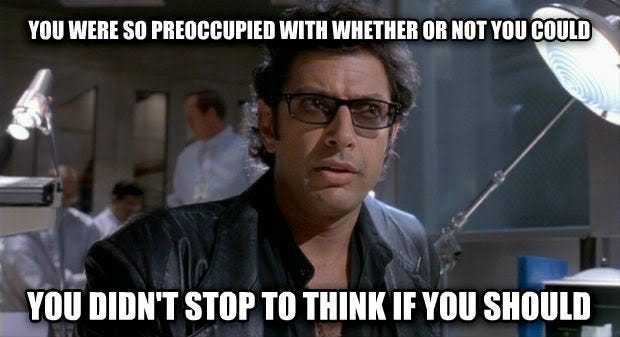

But we should also very much be asking ourselves whether or not we *should* be sending such messages.

Dark Forest Doom?

Is it possible that sending signals or physical messages into space is an act of existential doom?

While it feels rather poetic and perhaps even noble to send messages about ourselves out there for aliens, there is an active debate in astrobiology as to whether or not we should be sending such messages in the first place. For instance, given our knowledge of our own behaviors in the past when some technologically advanced human society has met a less technologically advanced human society, the question for sending out space messages is no longer just “Will anyone hear us?” but “What if someone does?”

This concern is at the heart of what’s now known as the Dark Forest Hypothesis, introduced in Liu Cixin’s science fiction novel The Dark Forest (the sequel to The Three-Body Problem). The idea is simple but chilling: just as animals in a dark forest remain silent to avoid detection by predators, intelligent civilizations may remain quiet because broadcasting one’s existence could be an invitation to destruction. In a galaxy where we cannot know the intentions of others—and where the consequences of encountering a hostile civilization could be total annihilation—staying silent might be the most rational and self-preserving behavior.

The Dark Forest Hypothesis is one possible answer to the Fermi Question, which asks why we haven’t yet seen evidence of extraterrestrial life despite the seemingly high probability that it should exist. Maybe the answer is: everyone’s listening, but no one dares speak.

Some critics of active messaging projects (sometimes referred to as “Active SETI”) argue that sending powerful, intentional broadcasts is akin to shouting our location into a dark and unknown jungle. They ask us to consider the cautionary tales of human history—how first contact between civilizations has often led to exploitation, conquest, or collapse. Not to mention, while we can’t assume that our own violent and dominative behaviors are universal, there’s no knowing the range of possible stances alien civilizations may have towards other life or other civilizations (and it could range from rather benevolent through utter disinterest to exceptionally cruel and violent). On top of this are also questions about our shared values in sculpting messages and who gets to speak for Earth and for all of us on our behalf.

I can highly recommend the work of my friends and colleagues, Julia DeMarines and Chelsea Haramia, on this topic. They have several great pieces exploring the science and ethical questions in regard to Active SETI, including The Imperative to Develop an Ethically-Informed METI Analysis and the book chapter An Ethical Assessment of SETI, METI, and the Value of Our Planetary Home. The end of their research paper on the imperative for an analysis of Active SETI projects before sending the messages is rather poignant to where we stand now:

There are sweeping ethical concerns at stake here, and these ethical issues are central to the formulation of proper METI policies at the political level, which have yet to be developed. The imperative to engage seriously with this debate and to develop ethically-informed METI policies and protocols arises not only from consideration of the risks and benefits involved, but also from actions currently undertaken by those with the power and technology to take the world’s future into their own hands. We must proceed with caution, and we must rely on the valuable input of others and of humanity itself as we move forward with the project of messaging extraterrestrial intelligence.

Much as with the not-quite-true claim that every disaster movie starts with a scientist’s warnings going unheeded, though, we’re still sending messages. Many groups, including METI International, are still sending messages right now and will likely continue to do so. But is there a true risk? Does it say something more about us that we’re currently progressing many technologies without in depth philosophical debate on a global stage (including AI advancements, biotech developments like “mirror life”, life extension and selective breeding, and even human space exploration)? What are the real concerns when a single person or a small group of people get to choose which messages to send on our behalf?

These truly are important questions for us to consider. And the sheer fact that not only could our messages be received and cause an alien civilization to come say “hi” (or maybe to aim their planet-destroying at upon the Earth) but that the messages we send also speak to who we are and how we will be remembered should be enough to warrant a larger global conversation.

But, as much as many of us wish we could have larger, rational discourse on the global scale around many topics, that’s just not happening with where we are now. And, like it or not, the technologies and tactics that could have serious repercussions are moving forward, requiring all of us who feel a vested interest to engage with these topics as best we can here and now.

And for everyone I personally know who is opposed to sending messages unchecked and without some guidance, there is someone else who feels that the benefits of having our messages received outweigh the risks. They often argue that any civilization capable of receiving and deciphering our messages may likely already be aware of life on Earth from our atmospheric composition, thermal emissions, or decades of radio and radar leakage. And I know a fair number of people who feel that if aliens are advanced enough to traverse interstellar distances, then they are likely also advanced enough to be guided by reason, cooperation, or empathy.

But we must acknowledge: these are all guesses. We have no evidence to suggest whether alien life—if it exists—would be peaceful, hostile, indifferent, or even comprehensible to us.

What’s clear is that the act of sending messages is not just a technical decision—it’s a profound philosophical one. It forces us to ask: What kind of civilization are we? Are we reckless or brave? Naive or optimistic? Are we trying to make contact—or simply leave a mark, a cosmic version of we were here, in case we’re gone before anyone might choose to swing by for a visit?

In the end, sending messages may be as much about who we are now as it is about who might hear us later.

Art, Archives, Beacons, and a Message in a Bottle

Even as we debate and consider the risks of sending messages into the cosmos, we continue to do so—not just with messages coded through math and science, but with our art, poetry, and imagination. We truly have been sending signals about who and what we are to the heavens.

These recent efforts reflect a different kind of hope: not necessarily to make contact, but to leave behind a trace of who we are—through both physical materials sent to space as well as messages sent to or from space.

A Sign in Space

In May 2023, artist Daniela de Paulis launched A Sign in Space, a global art-science collaboration that simulated the reception of an extraterrestrial message. Working with the European Space Agency, SETI Institute, and observatories around the world—including Green Bank and the Allen Telescope Array—the project transmitted an encoded signal from the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter back to Earth. The public was then invited to decode and interpret the message, sparking interdisciplinary discussions about how we might respond to a real signal from the stars. As an advisor to the project, I witnessed firsthand how this artistic simulation brought together scientists, artists, and the public in a shared act of cosmic imagination.

The Lunar Codex

Spearheaded by physicist and author Samuel Peralta, the Lunar Codex is sending over 30,000 works of art, literature, music, and film to the Moon aboard NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services missions. These time capsules, preserved on durable NanoFiche disks, are being sent on missions around the Moon and to Near Earth Objects, and some are even being deposited on the Moon.

MoonArk

Developed by Carnegie Mellon University, MoonArk is a lunar museum containing hundreds of images, poems, music, DNA samples, and even river water. The project aims to represent the diversity of life and culture on Earth. Sadly, a failure in the mission to the Moon ended up in a loss of the original MoonArk, but I wouldn’t be surprised if the group tries again.

Mikael Genberg’s Moonhouse

Swedish artist Mikael Genberg realized a 25-year dream by sending a small red house—a symbol of Swedish domesticity—to the Moon. It’s currently scheduled to arrive at the Moon onboard the lunar lander Resilience, created by the private Japanese company ispace, with a scheduled landing date of 6 June. Genberg views the project as a poetic gesture, placing a familiar human symbol in the stark lunar landscape .

LifeShip and the First Pyramid on the Moon

Ben Haldeman is an entrepreneur and creator of LifeShip, which offers opportunities for people to have their DNA taken to space. Just this year, the company achieved a beautiful feat in having the first pyramid placed on the Moon, onboard Firefly Aerospace’s Blue Ghost lander (which landed on 2 March 2025). The pyramid itself is rather small, fitting in the palm of a hand, but contains within it a variety of materials, including seeds, all of the information on Wikipedia, and lots of stories and artwork, including some stellar artwork by Amy Karle.

BEACON and the Message in a Bottle

Just as we’re sending artwork to the Moon and other realms in space, we also are actively thinking about what kinds of messages we may still send out there to aliens, whether as radio broadcasts or as physical messages. Recently, my colleague Jonathan Jiang has been bringing together teams to work on some of these new messages. These efforts have led to the papers A Beacon in the Galaxy: Updated Arecibo Message for Potential FAST and SETI Projects and Message in a Bottle—An Update to the Golden Record: 1. Objectives and Key Content of the Message (for which, I am a co-author).

Jonathan has argued more for a proactive stance in developing and sending messages. He’s even argued that perhaps communication with aliens may help us to correct some of our own issues here on Earth.

While I personally warrant more caution in sending digital messages out into the void (the forest could indeed be dark for a reason), I find value in working collaboratively on questions around what kinds of messages we would want others to receive and how the messages themselves speak a lot to our current hopes and ambitions, our past and our future, and what the process of evolution in the universe and on Earth has wrought for us here and now.

What Comes Next?

We’ve well entered into the space age, and yet we’ve only just barely dipped our toes into the cosmic ocean.

We may have seen the flights of Sputnik and Explorer, Yuri Gagarin and Alan Shepherd, the developments of Apollo and the Soyuz, the Space Shuttle and the International Space Station, and now a new realm of private spaceflight funded by billionaires taking a number of tourists into space, but still less than 800 people have gone to space as of today. That’s an extremely small proportion of the current human population.

We’ve begun a more intensive study of our Earth from space and our solar system. We’ve sent spacecraft to various worlds around the solar system for scientific exploration. And we’ve sent 5 spacecraft out with enough velocity to slowly travel into interstellar space and one day leave our solar system—Pioneers 10 and 11, Voyagers 1 and 2, and the New Horizons spacecraft are our only interstellar expansions so far.

And we’ve now been sending signals into the void, both unintentionally and intentionally, for many decades.

As our world continues to change and our technologies evolve, we may find even more radical ways to create messages about ourselves. Perhaps the next generation of space art on the Moon or Mars and the messages we send will include ever more data, simulations of a day in the life of a human or of our planet, humongous cultural libraries, or perhaps even the encoded blueprints of our DNA and how to create a human (imagine a future human waking up in an alien society and one day learning that the information that led to their existence was sent from a world far away). We may one day develop new physics that allows us to send messages with gravitational waves or to somehow impact the nature of spacetime such that we can send messages directly to other worlds without having to worry about the speed of light (no idea how that would be done—it would certainly require new physics that we don’t have right now).

No matter how we go about sending signals into space, the promising thing in my opinion is that some of us are trying to engage in the conversation about what to send, how to communicate on behalf of all of us as responsibly as possible, and even to remember that the question of whether or not we should send messages is actually rather important right now.

I, for one, am hopeful that if an alien civilization does receive one of our signals that it won’t lead us to destruction. Of course, there’s the chance that none of the signals we’ve been sending or will send anytime soon will be received in time for us to have any form of back-and-forth communication. It might truly be that the signals we’re sending will record across spacetime the growth and development and fate of the human species. No matter where we go from here, many of the messages and signals we’re creating and sending out there will outlast all of us by eons. Perhaps some day, many, many years from now, some intelligent beings will come upon some remnant—Voyager 1, an artifact we’d left behind, one of our messages traveling through space—and will come to know us at least a little bit. And I like to feel hopeful about what that might mean to them.