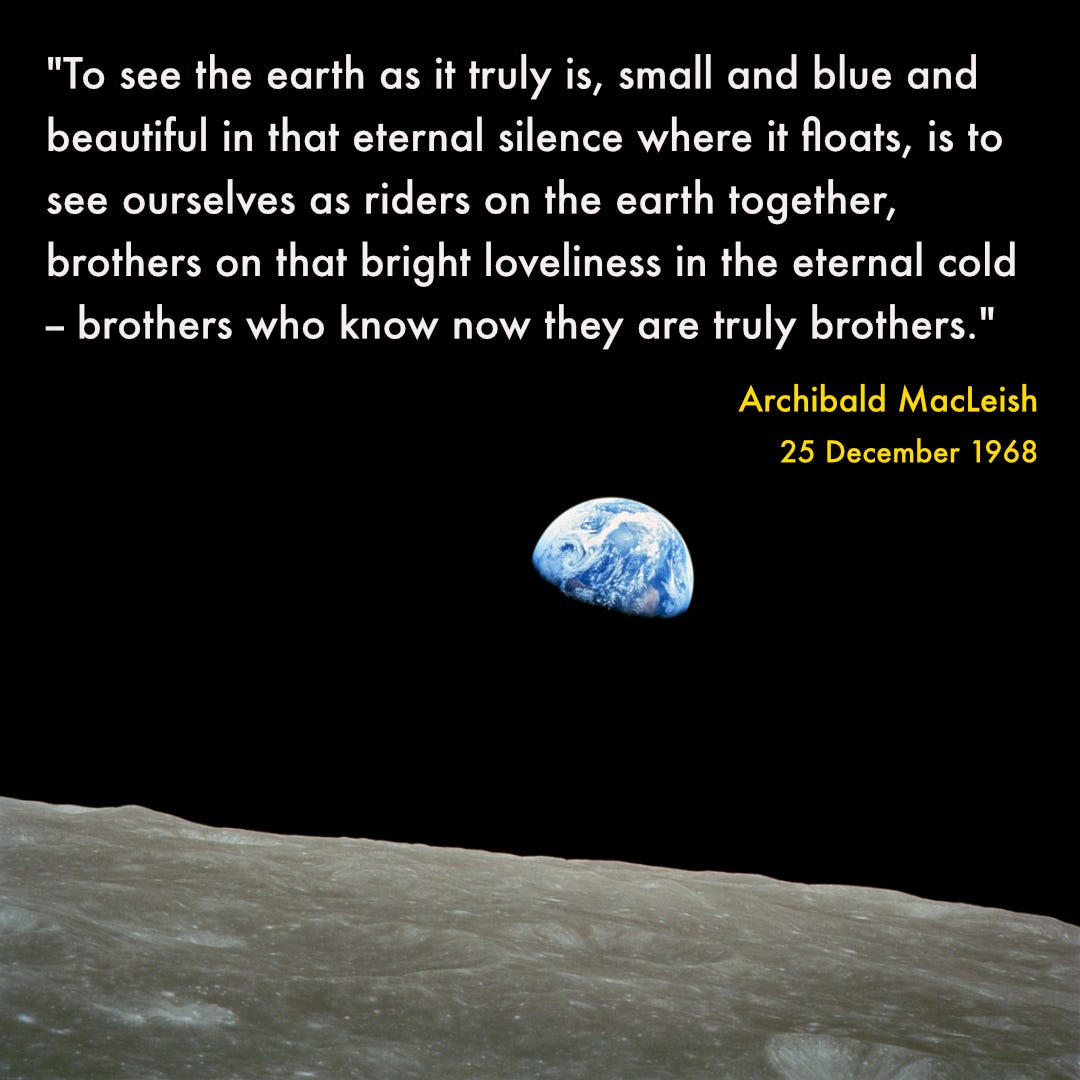

The iconic Earthrise image (above), captured by the crew of Apollo 8 in December of 1968, marked a turning point in our human awareness of ourselves and our place in the cosmos.

Although there had been earlier images of Earth taken from space and several astronauts had seen our world from beyond by that point, the Earthrise picture was one of the first that was shared widely by people around the entire planet (and perhaps the very first to truly have inspired a significantly large proportion of the population).

Earthrise in many ways drove a shift in perspective that reshaped our collective understanding of our homeworld. Previous authors and scholars and thinkers had dreamed of seeing our world in such a way, but seeing the Earthrise image and knowing that it was taken on a camera held by other humans transported those who saw it for the first time into new realms of thinking.

One such person who was inspired and transported by the Earthrise image was the American poet and lawyer Archibald MacLeish. Seeing the image drove him to pen a reflection on the importance of such views. His writing, A Reflection: Riders on Earth Together, Brothers in Eternal Cold, was published in The New York Times on Christmas Day, 1968 (read it in its entirety below).

MacLeish’s words encapsulate the transformative power of viewing Earth as a “small, blue, and beautiful” entity floating in “eternal silence.”

The reflective piece of writing echoes the sentiment of the emerging environmental movement of the late 1960s in the U.S. (and a return to ideals held by many indigenous tribes and people through time) and conveys the fragility and interconnectedness of life on this “tiny raft in the enormous, empty night.”

The writing below invites readers to confront the implications of this new vision: that we are not masters of the universe but rather “brothers” sharing a singular, irreplaceable home.

A Reflection: Riders on Earth Together, Brothers in Eternal Cold

By Archibald MacLeish, New York Times, 25 December 1968

Men's conception of themselves and of each other has always depended on their notion of the earth. When the earth was the World -- all the world there was -- and the stars were lights in Dante's heaven, and the ground beneath men's feet roofed Hell, they saw themselves as creatures at the center of the universe, the sole, particular concern of God -- and from that high place they ruled and killed and conquered as they pleased.

And when, centuries later, the earth was no longer the World but a small, wet spinning planet in the solar system of a minor star off at the edge of an inconsiderable galaxy in the immeasurable distances of space -- when Dante's heaven had disappeared and there was no Hell (at least no Hell beneath the feet) -- men began to see themselves not as God-directed actors at the center of a noble drama, but as helpless victims of a senseless farce where all the rest were helpless victims also and millions could be killed in world-wide wars or in blasted cities or in concentration camps without a thought or reason but the reason -- if we call it one -- of force.

Now, in the last few hours, the notion may have changed again. For the first time in all of time men have seen it not as continents or oceans from the little distance of a hundred miles or two or three, but seen it from the depth of space; seen it whole and round and beautiful and small as even Dante -- that 'first imagination of Christendom' -- had never dreamed of seeing it; as the Twentieth Century philosophers of absurdity and despair were incapable of guessing that it might be seen. And seeing it so, one question came to the minds of those who looked at it. 'Is it inhabited?' they said to each other and laughed -- and then they did not laugh. What came to their minds a hundred thousand miles and more into space -- 'half way to the moon' they put it -- what came to their minds was the life on that little, lonely, floating planet; that tiny raft in the enormous, empty night. 'Is it inhabited?'

The medieval notion of the earth put man at the center of everything. The nuclear notion of the earth put him nowhere -- beyond the range of reason even -- lost in absurdity and war. This latest notion may have other consequences. Formed as it was in the minds of heroic voyagers who were also men, it may remake our image of mankind. No longer that preposterous figure at the center, no longer that degraded and degrading victim off at the margins of reality and blind with blood, man may at last become himself.

To see the earth as it truly is, small and blue and beautiful in that eternal silence where it floats, is to see ourselves as riders on the earth together, brothers on that bright loveliness in the eternal cold -- brothers who know now they are truly brothers.

Earthrise and Perspective

MacLeish’s reflection is more than poetic; it’s philosophical.

His writing explores how the image of Earth from space alters humanity’s sense of self—certainly articulating early visions of the Overview Effect and how seeing ourselves from the outside changes us.

Historically, humanity has often defined itself based on its place within our conceptions of the universe.

In much of the medieval world in Europe, humans were central actors in a divine plan. The scientific revolution shifted that narrative, casting humanity in a much different light in the face of vast, indifferent cosmic forces. Carl Sagan would later refer to these changes in our viewpoints as The Great Demotions—though his writing also explored how these changes were not necessarily steps towards insignificance (a topic I’m working on now as well).

The Earthrise photograph offers a transformative perspective: it underscores our shared humanity and fragile interdependence. It highlights for many the very fact of our cosmic significance—we may not be ordained to greatness by the deities of old, but we are now the cosmos coming to learn more about itself, with our venturings out into the void beyond our world one small step in a collective future for all of life as we know it.

When viewed from space, Earth appears devoid of borders, hierarchies, and divisions. This perspective forces us to confront the somewhat arbitrary nature of human conflicts, territorial disputes, and the destruction wrought by war—while truly impactful and meaningful to those who live through such atrocities (and the lives lost along the way), our squabbles have taken place in the blink of an eye in the scales of time of the cosmos.

Earthrise, and subsequent images like it, invites us to reconsider the ecological and moral responsibilities that come with being the inhabitants of this “tiny raft in the enormous, empty night.”

Key Themes in MacLeish’s Reflection

The Shift in Self-Perception

The medieval view placed humans at the universe’s center, while the modern industrial view of the time relegated them to mere victims of chance. MacLeish’s vision proposes a third perspective: humans as stewards of Earth, united in shared responsibility and kinship.

Interconnectedness of Life

The idea of being “riders on the earth together” suggests that all life is interconnected, reinforcing the urgent need for unity in addressing global challenges like climate change, resource scarcity, and geopolitical conflicts.

The Fragility of Earth

By describing Earth as “small, blue, and beautiful,” MacLeish emphasizes its vulnerability. The juxtaposition of this fragile beauty against the “eternal cold” of space underscores the imperative to protect and cherish our home.

A Call for Unity and Stewardship

The Earthrise image and MacLeish’s accompanying reflection remind us that the boundaries and divisions we construct are truly insignificant in the grand scheme of the cosmos. We have far more in common than what keeps us apart (and the same can be said for all of life on Earth as we know it), but we also should find value in our differences. As Sanjoy Som has articulated, “the beauty in humanity lies in its diversity, the realization of which is another key to the longevity of our civilization.”

Recognizing our shared humanity and fragile place in the universe offers hope for a more compassionate and sustainable future. Visions of Earth rising above celestial horizons inspire us to be more together.

We are, indeed, “riders on the earth together,” and in that shared journey lies the potential for profound change.

This is a revamping of an older post from 2019 that I’d shared on A Cosmobiologist’s Dream (my rather old blog from Blogger).