Is the Habitable Zone Really Habitable?

Is it worth fighting over a term that might be misleading in science?

The allure of discovering life beyond Earth has popularized the term "habitable zone." But it’s also made things a little challenging for science communication, since anyone trying to honestly and effectively communicate about the science has to also describe how being inside or outside of this zone doesn’t tell us all that much about habitability of a planet.

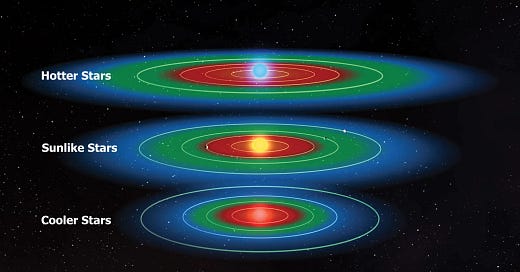

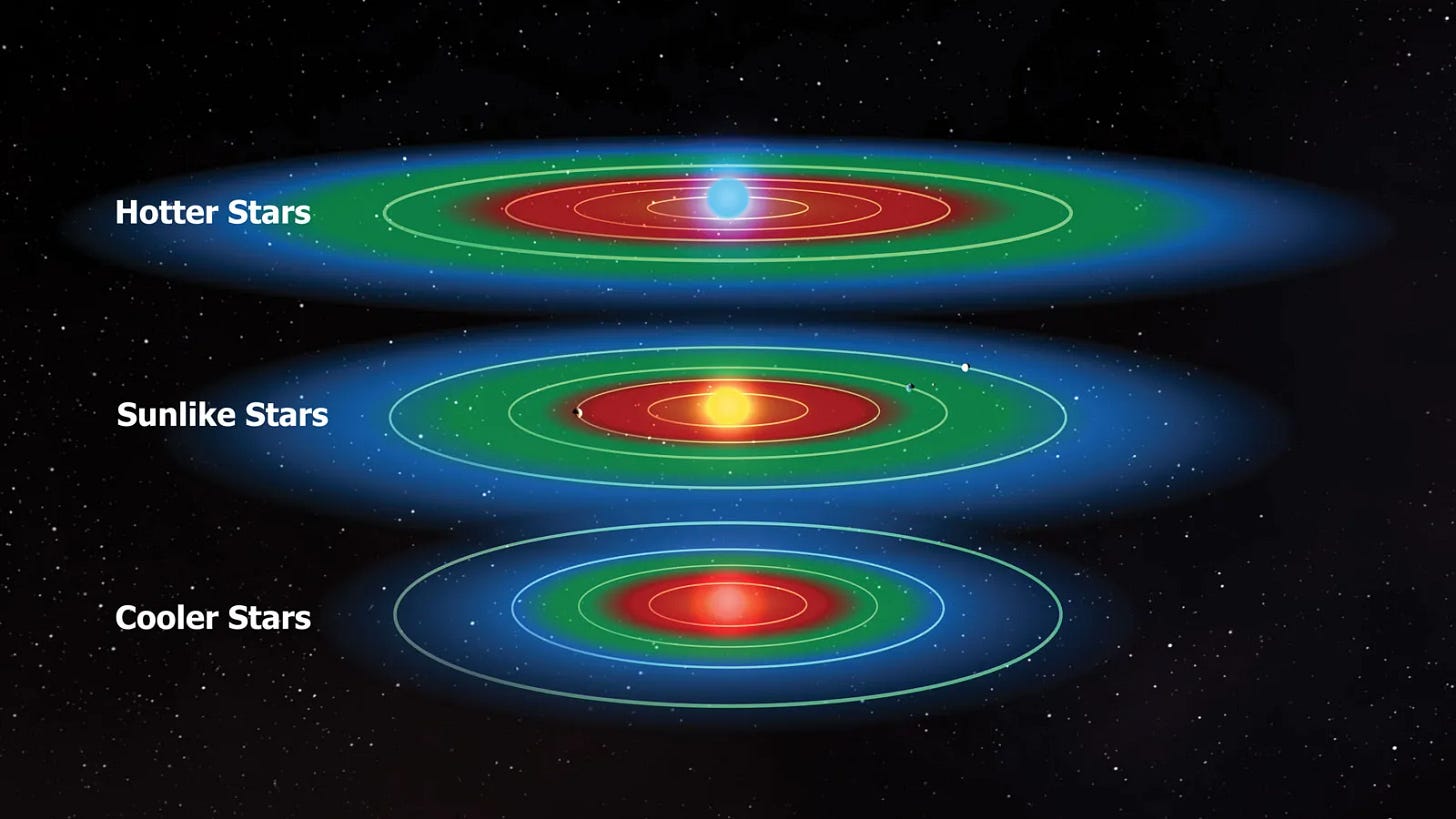

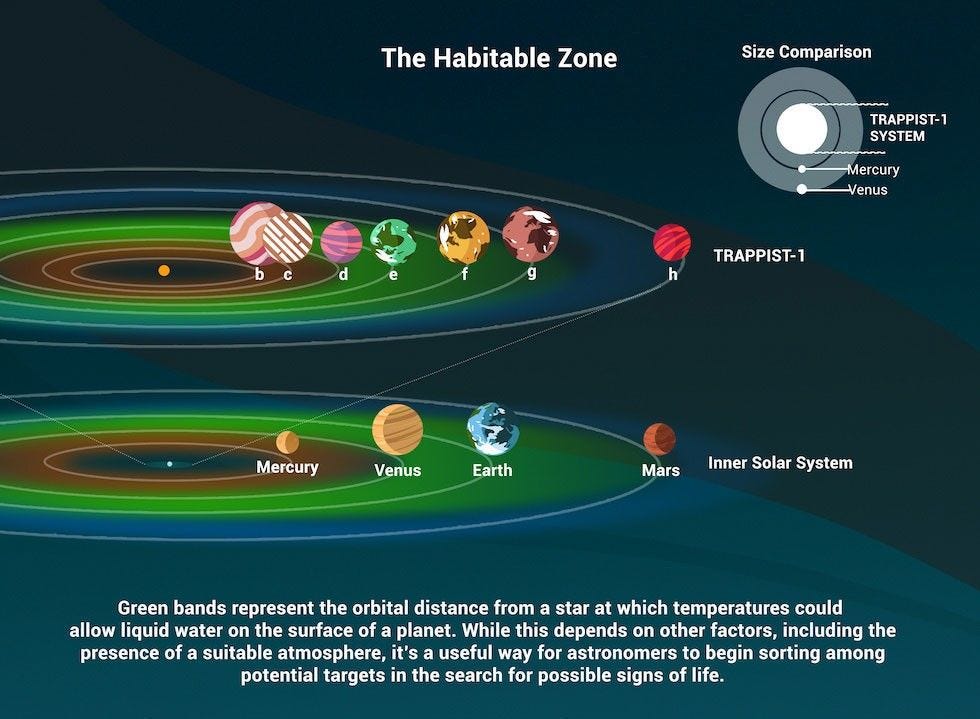

The habitable zone is the region around a star where a rocky world might potentially have liquid oceans at its surface.

While the habitable zone is a useful starting point in the search for life-supporting planets, it's essential to recognize its limitations. A comprehensive assessment of planetary habitability requires considering a multitude of factors beyond mere location within this zone.

But are there any alternatives? Is it worth even arguing about it? Let’s discuss!

Academic Chatter

Every realm of human study comes with its own vernacular and jargon.

In specialized fields like law, business, and medicine, technical jargon can sometimes serve to streamline communication among experts, but it can also obscure meaning or even mislead those who don’t fully comprehend the nuance.

In law, the “fruit of the poisonous tree doctrine” refers to evidence obtained illegally and is therefore inadmissible in court (the common example is if a police officer pulls over a person for speeding but then conducts an illegal and unwarranted search of the vehicle and finds illicit substances). While evocative, the phrase can be misleading—it suggests a kind of moral rot, but its legal function is procedural, not ethical, and it doesn’t always apply uniformly. Some jargon in law has grown so bad that we even tend to call the overuse of it “legalese.”

In business, terms like “synergy” or “disruption” can sound innovative while masking vague or hollow strategies (they’ve mostly become buzz words for “business as usual”). Even worse, sometimes in business (and other realms) people love to use sports metaphors like “slam dunk”, “monday morning quarterback”, and “out of left field”, but as Jan reveals in The Office, some of those metaphors are actually used in confusing and inapt ways: “Par for the course is a golf term. It means right on track. Uh, below par means worse. Wait, that should mean better. That doesn't make sense.”

We can see this in medicine as well. Medical jargon is known to be misleading to many people outside of medical fields, including phrases like “progress” (the disease is getting worse not better), a “positive test result” usually meaning something negative, an “impressive chest X-ray” is actually a bad thing, or how “grossly intact” on a neurological exam is actually a very good thing.

Maintaining the use of misleading jargon terms, even if useful for the professionals and specialists who understand their use and meaning, can potentially distort and mislead public understanding or even impact policy decisions in ways that are harmful to society.

The argot of science and specific fields within science is no different.

The term “junk DNA” long implied that non-coding regions of DNA had no function, which contributed to decades of underappreciation of their regulatory and structural roles and importance for evolution.

The “Big Bang” evokes an explosive event in space, but there are different ways that the term has been used to mean that singularity event at the beginning of the universe, the expansion of the universe, and a specific model for the expansion of the universe. Sabine Hossenfelder writes of this issue in the article, The Trouble With “The Big Bang.”

The phrase “missing link” in evolutionary biology has been exceptionally problematic, implying a single, pivotal fossil in a linear chain of human evolution, when in reality evolution of life as we know it has been a branching, complex process with many transitional forms. The false concept of a “missing link” ties into late 19th century thinking about “The God of the Gaps.”

In speleology (the study of caves), the jargon can be especially obscure—terms like “speleogen” and “vadose zone” are not only opaque to outsiders but also inconsistently used by researchers themselves, as highlighted in a New York Times article on the linguistic thickets of cave science: Are You Confused by Scientific Jargon? So Are Scientists. The article starts by sharing the jargon terms “polje, nappe, vuggy, and psammite” (I legit have a doctorate in geology, and I only knew what one of those words meant when I first read the article).

Of course, perhaps the most important term from science that means something entirely different to the general public is “theory.” In science, when we talk about a theory, we are discussing a concrete and well-defined model of how some feature of the cosmos works that has been tested and contested and has continued to fit our observations and inferences. But in the general public and media, the term theory is often used in a way that is synonymous with a “guess” or some random idea. In reality, the better term for the public to use if they want to sound scientific would be hypothesis—so on some cop drama show during the investigation, instead of saying “what’s your theory?” they could say “what’s your hypothesis?”.

Beyond theory, there are other important science words that are commonly misused or have different meanings in public life. “Law, model, significant, chemical, and proof” are among them. But there are many more terms that can be misused or can be misleading.

These examples show how specialist language, while sometimes useful within expert circles, can inadvertently shape public understanding and even the direction of research itself. In our modern day, we are continually flooded with examples of public misunderstanding of science, policy decisions negatively impacting science due to the ignorance of our politicians, and scientific jargon itself being intentionally misused by those who are peddling non-scientific ideas.

As Carl Sagan once wrote:

We live in a society exquisitely dependent on science and technology, in which hardly anyone knows anything about science and technology

If scientists want the public to better understand our work, and maybe even learn a bit more about science along the way, then it behooves us to do our best to communicate in ways that aim for understanding and to work together to abandon or avoid misleading, presumptive, or outright wrong terminology.

And, as I’ve argued, that includes the term “habitable zone.”

Exploring in the Habitable Zone

The term "habitable zone" (HZ) describes the region around a star where conditions might be just right for liquid water to exist on a planet's surface.

Without going into the math here (and there are some variations in how the region is defined), it’s basically a way of saying, based on the output of energy from a star, there is a region around the star where a terrestrial type of planet (a rocky world like Earth or Venus) wouldn’t be so hot as to basically cook off any liquid surface water nor so cold as to have any surface water be in a frozen state (ice). It’s a region where rocky planets could possibly have surface oceans.

The zone is different for different stars—depending on the radiation they emit. For instance, the now famous TRAPPIST-1 system has 7 exoplanets that have been observed. These worlds are all roughly similar in size to Earth, which is pretty awesome. While only some of them lie within the HZ for their star, it’s a much smaller star and these worlds are all super close to their star compared to the terrestrial worlds of our solar system.

The Habitable Worlds Catalog, managed by the Planetary Habitability Laboratory, currently lists 70 known exoplanets (out of the 5,000+ that we’ve found so far) that are known to be within the HZ for their star systems. And, as you’ll often see in the media, it’s believed by some researchers that these kinds of worlds within their host stars’ HZ might be the best to explore when it comes to looking for signs of alien life.

But is that true? Are the worlds in the HZ the most likely to have signs of alien life that we can detect?

Habitable Worlds in the HZ

The word “habitable” in the term “habitable zone” means something different than the actual word itself.

The word “habitable” itself refers to something that is generally suitable for living within or suited to habitation by humans or other beings. We might refer to a nice house as habitable. In most conversations about human life we’re probably more likely to hear the negative of the term—as in “that house is so deteriorated that it’s become uninhabitable”, “after the nuclear weapon detonated, the area became uninhabitable for years”, or “if we don’t do something about our impacts on the climate, our own planet might become uninhabitable for humans.”

When we think about alien worlds that might be habitable, we’re really thinking about the types of environments where life as we know it (and maybe life as we don’t) could potentially emerge and evolve.

Our thinking about these possible habitable environments and habitable worlds has changed over time. In the early 1900s, it was thought by a lot of people that Mars and Venus were both habitable for human-like beings—we now know that’s not at all true. But there are many of us who are now wondering about other worlds much unlike the Earth—could icy moons with oceans like Europa or Enceladus have habitable regions within their deep ocean interiors? What about more extreme environments, like the gassy atmospheres of giant exoplanets that are more like Jupiter and Saturn?

As of now, there are many researchers who think it might be most valuable to set our sights first on worlds that have as much in common with our own as possible. And that’s why the worlds of the HZ are so interesting to astrophysicists and astrobiologists.

But being in the HZ says nothing about whether a world within the zone is actually habitable or not, and it doesn’t even tell us if the worlds in that region are Earth-like or not.

Some rocky worlds with oceans might not have life, and we have no idea as of now what proportion that might be likely to be. While there are many people who think that having oceans was one of the key factors to the origin(s) and evolution of life on Earth, we don’t know for sure if life can start in oceans and some researchers, like Bruce Damer and Dave Deamer, have even suggested competing ideas for why life might need dry land with wetting and drying cycles to get going. So having a rocky world with an ocean is not a guarantee that the world is habitable for any form of life.

Being in the HZ also doesn’t mean that a rocky world will indeed have an ocean.

Perhaps some HZ worlds never had sufficient sources of water. Perhaps there are others that had a runaway greenhouse effect like Venus and their surfaces are sweltering hellscapes lying below thick atmospheres. The HZ is simply the region around a star where the orbital position of a planet means that if the conditions are right it *could* have liquid water at its surface.

Also, with our current knowledge, we can’t remotely say that any worlds outside of this HZ are thus uninhabitable. We may one day find that icy moons with deep oceans tend to be more habitable for a wider range of life, or maybe that atmosphere dwelling beings on much larger worlds are far more common than the life we have here on Earth (I don’t personally think that will be the case, but my own feelings don’t preclude possibility).

As Elizabeth Tasker and her colleagues shared in their article, The language of exoplanet ranking metrics needs to change, published in 2017:

“We have found many Earth-sized worlds but we have no way of determining if their surfaces are Earth-like. This makes it impossible to quantitatively compare habitability, and pretending we can risks damaging the field.”

Of course, there are a range of opinions regarding the use of the term.

For fun, I ran some polls on X and LinkedIn to ask people what they thought about the term. Here are the results:

This certainly isn’t any kind of representative sample, just a couple of fun polls. Of the 31 votes on the X post and the 112 votes on the LinkedIn post, there were certainly a range of opinions. And the language I used in sculpting the posts might have been a bit suggestive itself (the opposite of useful is not misleading, but I really wanted to see if people understood what the term even means and how they would respond to suggestive language—it might be fun in the future to run a larger poll about beliefs and ideas around alien life with the language sculpted for a better analysis of the responses).

And there were some awesome comments and discussion on these posts. Some of my favorites are:

And there are certainly many other opinions to be had if I had polled a larger number of people.

It is worth pointing out that as of the time of this writing, the term “habitable zone” is well-entrenched in the parlance of astrophysics and astrobiology. But I think we should still actively discuss its value and whether it might be misleading.

One thing I like to do in some of my talks is ask people if they know what the habitable zone is, and, anecdotally, I have noticed that many people outside of the space sciences are indeed very misled by the term—one of the most common responses I get is that people think that it means the region around a star with Earth-like worlds (which, again, is not correct).

Should we continue using a term that can be misleading? If we don’t, what other terms might we want to use?

Alternative Terminology

Being in the habitable zone does not inherently make a world habitable. Nor does being outside of the HZ mean that a world is uninhabitable.

On top of that, being habitable does not mean that a world will necessarily be inhabited.

A nice new home built in your neighborhood might be habitable, but that doesn't mean anyone is certainly living there (yet). It wouldn’t be until you find actual evidence of someone living there—lights at night, cars in the driveway, the same people coming and going, you stopping by with a baked dessert and a welcome message—that you could say you now have new neighbors.

But is the term habitable zone problematic enough that we should use different terminology?

Admittedly, I don’t know. It might not really matter all that much. But it seems like if the terminology we use in our hunt for alien life is presumptive and potentially misleading, then it’s worth at least considering alternatives.

One of the most common alternatives is Goldilocks Zone. Using the terminology from the old fairy tale, where Goldilocks had porridge that was too hot, and then too cold, and then just right, Goldilocks Zone speaks directly to the actual physical definition of that region of space around a star.

However, as some have pointed out, there are issues with relying on a fairy tale for sourcing the language we use to describe a scientific concept. Even though the worlds of our solar system, our constellations, planetary features, and more have been named for beings and ideas from mythology and literature for a very long time, many people feel moving forward like we should abandon using our old stories to name things.

There are other examples of words from mythology and literature being used in modern science and journalism regarding science, including Gaia Hypothesis, Frankenfood, Chimera, Trojan asteroids, Yoda conditions, and Skynet scenarios. We often allow a variety of terms from our storytelling to guide how we communicate various concepts. But perhaps we want to be more inclusive of all of humanity in creating scientific terminology and avoid stories from specific regions. In that case, there are also other possible terms we could use.

Tasker and her colleagues recommend the term “temperate zone” in their paper. Much like Goldilocks, the term “temperate” applies to the temperature being just right for liquid water, without any presumption of habitability.

My friend, Sonny Harman, shared with me the concept from Frank Selsis of using “hunting zone” since we’re focusing a lot of our current searches for possible alien biospheres in this region.

Honestly, Goldilocks zone, temperate zone, and hunting zone all have their own issues, but at least none of them presumes habitability.

Does this really matter?

As Paul Gilster in Centauri Dreams writes in his article Is the Term ‘Habitable Zone’ Viable?, which he wrote after Elizabeth Tasker and colleagues published their 2017 article:

By all means, go to ‘temperate zone’ within the scientific community if necessary — it makes no claims about ‘habitability’ – but I suspect our problems with foolish headlines are going to remain a part of the public experience. It takes patience to keep explaining the limitations of exoplanet science, and telling that story accurately isn’t always the way to maximize an audience. But fatigue with exaggerated headlines coupled with persistent education on these matters may eventually right the balance.

Paul argues, and probably rightly, that we might not be able to change the language. The words and terms we use evolve to fit how we use them, and even if the term “habitable zone” is misleading and comes with baggage, it might just be where our vernacular is going. We might be long-term altering the nature of the term “habitable” itself by maintaining the potentially misleading language, but that might not be the worst thing.

And, of course, arguments about the habitable zone aren’t the most prevailing linguistic issue in astronomy right now. That is most certainly the eminent position of the arguments about the word “planet.”

Is it worth fighting over how we use potentially presumptive and misleading language in science? I personally think so, but I might be among a minority, especially at a time where there are some pressing issues to how science is funded and supported by the public (especially here in the U.S.).

Even if we keep using the term “habitable zone” to describe that region around a star, I’ll still be over here trying to help people outside of the space sciences to understand what that term really means and why it has nothing to do with habitability.