Into Futurity: Traveling the Tangled Threads of Time

Time, stories of time travel, and alien perspectives in time and space.

Time is, at once, one of the most familiar things we experience and one of the most elusive.

We live embedded in time, shaped by its passage, and constantly aware of its flow—and yet when we begin to ask what it actually is, the answers become rather slippery. Is time a fundamental feature of the universe? A construct of our perception? A stubborn illusion?

One question that I often consider: is the perspective of time something universal, or will alien civilizations have radically different experiences of time?

We’ve had various ideas about what time is through the course of history, and it’s a topic that’s still being debated. And we’ve also wondered if we ourselves might be able to travel through time faster than our evolution has allowed—basically jumping from one place in time into another. But is time travel really possible? And what happens if we meet aliens who really do perceive time differently than us?

The machine of time

Concepts of travel to discrete periods of time have appeared in human storytelling for quite some time (see what I did there?).

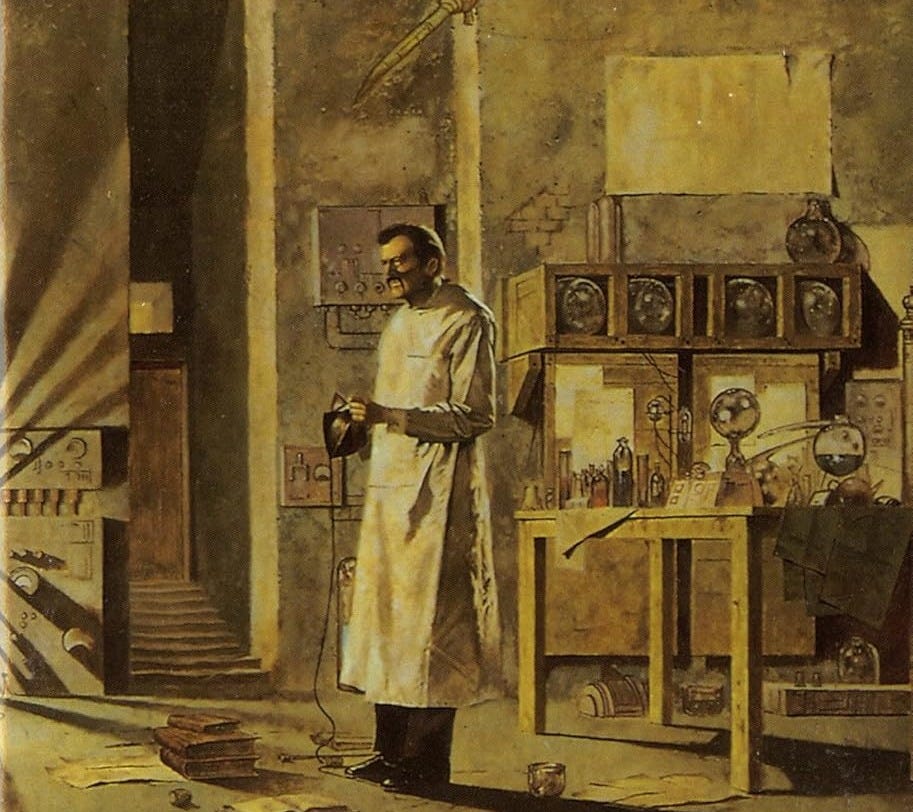

But the concept of using a technology, a machine, to travel in time might first have been explored by American writer, Edward Page Mitchell, in 1881 with his short story The Clock That Went Backward in 1881. In this story, a mechanical clock is the device that allows for travel through time.

Spanish writer Gaspar, who wrote El Anacronópete in 1887, also has an early claim on using a mechanical device for time travel. I love that the first chapter of his work is subheaded with “In which it is shown that moving FORWARD is not the hallmark of progress” (“En el que se prueba que ADELANTE no es la divisa del progreso”).

Of course, though, most people are far more aware of the story published nearly a decade later by H.G. Wells—The Time Machine. Published in 1895 (and, intriguingly, unlikely to have been inspired by the earlier and lesser known works by Mitchell and Gaspar), The Time Machine set the “gold standard” for not only having a device for time travel but also allowing its user to control the place in time to which they are traveling.

Wells’ story is certainly well known for its impact in science fiction stories of time travel, but also for its exploration in the realm of stories of a future where the split between the “haves and the have-nots” grows so large as to cause the development of a dichotomous civilization (as we see in the story of the Eloi and the Morlocks).

There are two specific lines from Wells’ short story that have stuck with me for years (and reinforced by several re-readings). One of them is referring to the travel to the future as “into futurity” (which is just a cool way to phrase it). And the other is to consider how we perceive time:

There is no difference between Time and any of the three dimensions of Space except that our consciousness moves along it.

Experiencing time is to move in time and space. Even if we’re sitting in the stillest depths of meditation, there is still action and activity happening within and around us. We honestly don’t know (or can’t know) what it would be like to experience time as solely a movement of our consciousness without some activity in space, which would argue against Wells’ perspective (as shared by the narrator in the story). Yet, Wells’ was onto something in considering time as another dimension of the physical universe along with space.

In contemporary physics, time is understood as a dimension intertwined with the three (or perhaps many more) dimensions of space, forming a four-dimensional continuum known as spacetime. This concept was first proposed by mathematician Hermann Minkowski in 1908 to describe how space and time are unified.

Einstein's theory of special relativity in 1905 revolutionized our understanding by demonstrating that measurements of space and time are relative to the observer's state of motion. Two key postulates underpin this theory: the laws of physics are the same in all inertial frames, and the speed of light in a vacuum is constant for all observers, regardless of their relative motion. These principles lead to phenomena such as time dilation, where a moving clock ticks more slowly compared to a reference stationary one, and length contraction, where objects in motion are measured to be shorter along the direction of motion compared to a reference stationary perspective.

General relativity, which Einstein first published in 1915, further extends these concepts by incorporating gravity into the spacetime framework. It posits that massive objects cause spacetime to curve, and this curvature influences the motion of other objects, which we perceive as gravity. This curvature also affects the passage of time, leading to gravitational time dilation, where time passes more slowly in stronger gravitational fields. For instance, clocks closer to massive bodies like Earth tick more slowly than those further away. This is why it’s argued that the center of our planet is a few years younger than the surface.

With Einstein's special and general theories of relativity, time became malleable. Clocks tick more slowly near strong gravitational fields and for fast-moving observers. Time is not absolute but local, tangled with space, relative to perspective. But these effects, while real and measurable, still do not allow for the kind of movement that Wells imagined. The arrow of time—the relentless push from past to future—remains unbroken in our experience.

Do you have the time?

The nature of time has been a subject of inquiry in both philosophy and science, leading to a diverse range of ideas and interpretations.

Some have considered whether the past, present, and future are even real. Presentism posits that only the present moment is real, with past and future events being nonexistent outside of our mental conception. In contrast, eternalism holds that all points in time—past, present, and future—are equally real, suggesting a block universe where time is akin to a spatial dimension. The growing block theory offers a middle ground, proposing that the past and present are real, while the future remains open and undefined. And, of course, these concepts play into the arguments of free will vs. determinism—do we live in a universe that is already predetermined, where all causes and events could be calculated by a sufficiently advanced (god-like) computer? Or is the future really an “undiscovered country” (to use Shakespeare’s term for the unknown of what happens (or doesn’t happen) after death), where things from the present moment may come to fruition depending on what we do now?

There are various scientific considerations of what time might be (if it is even real). Stephen Wolfram argues for a computational view of time—whereby “Time remains that computational process by which successive states of the world are produced.” This view of time as a computational process also speaks to the conception of our lineage of existence in the cosmos (which Sara Imari Walker spoke of on Ask an Astrobiologist). In quantum mechanics, time also takes on a different conception than in classical physics, and suggests that time might not be a fundamental entity but rather an emergent phenomenon arising from the processes of the universe.

There are many questions about the nature of time, but for all of our pondering, the one thing we haven’t figured our way around yet is the fact that time appears to flow from the past to the present to future—there is an arrow of time. In a podcast for Quanta Magazine, Frank Wilczek explained of the arrow of time:

It’s a long story that has gotten more and more convincing over time. But I think there are apparently many different arrows of time, many different ways in which the future is different from the past. There certainly is a psychological phenomenon. Also, the second law of thermodynamics. It tells you that things become more random, very roughly speaking, but also has a precise formulation. There’s the radiation arrow of time, that radiation tends to go out from things and not come in. There’s this arrow of time associated with evolution of life. And many others you could invent on the fly. Everywhere you look, there are arrows of time. There are asymmetries between the future and the past.

But I think all of them now — we can wrap them all up into one arrow. Just like the “One Ring that rules them all,” there’s one arrow that rules them all, and that’s the cosmological arrow of time.

We might not be entirely sure what time is, but from our experience of the cosmos, time is something that progresses. We flow along with time.

As Sean Carroll shared in his talk during XPANSE last year, “There’s nothing more important to our experience of the universe than the passage of time.”

The universe carries on and we carry on with it, at least in our perspective.

And yet, we’ve wondered what it might be like to break through time and our perspectives of it. We’ve wondered about jumping from one place in time to another through time travel.

Travelers in time

Science fiction has long served as the laboratory for testing time travel concepts and presenting the many bizarre problems that we can thus far imagine if one were to jump from one place in time to another.

From paradoxes to branching timelines, from ancient ruins to future empires, we return to this theme of jumping in time again and again. Why? Perhaps because time travel stories force us to reckon with cause and effect, fate and free will, and our deepest hopes and regrets.

Stories like Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut show us what it might feel like to become "unstuck in time," where the protagonist Billy Pilgrim experiences past, present, and future moments in a nonlinear stream. The narrative presents time as an ever-present dimension, and raises questions about trauma, agency, and determinism. Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker also considers perspectives of time, as the narrator journey’s through scales of spacetime on their cosmic transition through the universe.

There are also lots of stories that consider the psychological or biological impacts of moving from one place in time to another. In The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, adapted from F. Scott Fitzgerald's short story, we explore the psychological and social consequences of a man aging backward. Though not a traditional time travel narrative, the reversal of biological time creates emotional dissonance and existential weight, as relationships drift against the tide of age.

In films like Infini and Devil's Pass, time travel introduces mental and physical distortion. Exposure to temporal shifts can lead to psychological breakdowns, memory fragmentation, or bodily mutation. These stories suggest that moving through time in unnatural ways may carry profound biological consequences—a kind of temporal radiation sickness (something Michael Crichton also introduced in his novel Timeline).

Ever since the early works of Gasper and Wells, authors and filmmakers have been considering what kinds of machines or technologies may allow for time travel. Wells' original time machine is never described in rigorous detail, but later fiction offered more imagined specifics: tachyon drives, wormhole gates, quantum tunnels, or even consciousness-transfer devices that sidestep physical time travel in favor of mental projection. From Doc Brown's DeLorean in Back to the Future to the temporal displacement equipment in The Terminator, the narratives often hinge on whether one can safely navigate or alter past events. This brings us to the classic "Grandfather Paradox": if you travel back in time and prevent your grandfather from meeting your grandmother, do you cease to exist?

We see a humorous but insightful take on this idea in The Simpsons Treehouse of Horror segment "Time and Punishment," where Homer accidentally alters the future through minor actions in the past.

Similarly, The Butterfly Effect film explored how small changes in the past can drastically reshape the future, creating cascading consequences. The tension between changing the past and the unpredictability of doing so is a recurring theme in these tales.

Some stories avoid using physical jumps in time, instead asking what might happen if we could observe the future. A good example of this is Paycheck, a film based on Philip K. Dick's short story, where the manipulation of future knowledge invites a practical, if chilling, vision of time travel. It's not a machine that takes you physically into the future, but rather a way to peek ahead, selectively, and exploit causality. This dovetails with our real-world obsession with prediction, risk, and control. What if we could know the outcome before we act? What if hindsight became foresight? Do we have what it takes to act responsibly if we had some knowledge of what our future might be?

Honestly, time travel stories often seem so riddled with paradoxes and conceptual issues that they should make us wonder if we would even wish to travel in time if we could. But they do make for fun storytelling and have been good tools for inspiring everyone to think a bit more about the nature of time itself.

However, I can’t help but wonder if maybe our thinking of time isn’t the only kind there is. How might aliens perceive time?

Time and time and time again

In the film Arrival, based on Ted Chiang's short story "Story of Your Life," time becomes something more tangible.

The aliens in the story experience all of time simultaneously. For them, cause and effect are not linear but holistic. Their language reflects this, as does the mental rewiring experienced by the human protagonist. The story itself uses the alien visitation and communication as a means to consider deeper questions—what if we could perceive time not as a linear progression but as a landscape, and could adapting to language from such a perspective reshape human cognition to view time differently?

We certainly can’t know the answer to the latter currently, but there are some possible differences in how aliens could perceive time that might altogether impact their own language and culture and technological developments and more. For instance, if their biology evolved under different planetary and geological cycles, or if their consciousness formed in a radically different way, would they think of time as we do? Would they measure it? Would they experience it? Could they live in multiple moments at once, or in vast, slow pulses spanning millennia?

Our human view of time is tied to our biology—our circadian rhythms, our memories, our brief lifespans. But time, as a concept, might not be universal. It could be as varied as the number of possible planetary environments in which life may take hold (though I’d bet there are some convergent processes in regard to time perception). And if perception of time is not inherently fixed, but a dimension of awareness, then exploring it—scientifically, philosophically, or fictionally—is not just about machines or paradoxes. It's about the deepest aspects of what it means to be conscious and aware of the cosmos.

Time travel may never be a scientific reality, but it remains a powerful metaphor for considering the impacts of this thing we all share. We all travel in time, whether we want to or not. We carry the past within us, dream of the future, and experience the strange, fleeting now. Stories of time travel and alien perceptions of time give us ways to reimagine regret, wonder, possibility, and the limits of our own perception.

While it seems like time is part of space and we are all at once traveling in both space and time, perhaps there’s a bit more truth to Well’s conception that it’s our consciousness that travels in time. Maybe, one day, we’ll meet some aliens who experience time differently or maybe even integrate with our AI/AGI in such a way that it alters our own views of time. Perhaps one day we’ll discover that we can travel farther in/through/with/outside of time than we’ve ever imagined.