Echoes of the Self: Consciousness and Identity in SOMA, Star Trek, and Altered Carbon

Can we upload a human consciousness into a computer, robot, or other human body? Would we want to?

The Many Questions of “Uploading” the Self

I just recently finished playing the game SOMA for the first time.

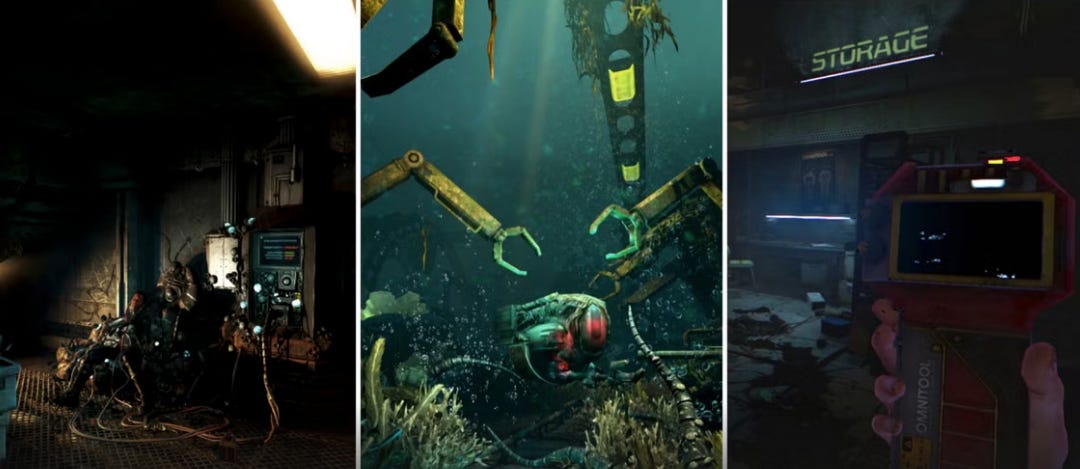

Released in 2015 by Frictional Games, it’s a fun sci-fi horror survival game where the protagonist, Simon Jarrett, finds himself “waking up” in a far future where he’s alone deep under the ocean in a facility where remnants of humans are trapped in the bodies of robots or have become humanoid monsters. The walls of the facility ooze over with a cybernetic mix of what appears organic and machine (later finding it to be the outgrowth of an AI system called WAU which is trying to keep the human contingent alive by integrating them with its own materials). Along the course of the game, the main character has to solve puzzles and avoid the monsters to find out how he came to be there aa well as to help out someone he meets along the way—and then to “escape.”

One key theme that comes up in the came is the concept of separating a human consciousness from its body, to be either uploaded into another body or form or to be stored within digital and/or virtual formats. Basically, the concept of “uploading a consciousness” (sometimes called “consciousness downloading” or “mind uploading” and other terms).

This has come up a lot in science fiction as well as in the philosophy of consciousness and neuroscience.

Is it possible that we might one day understand human consciousness well enough that we could take whatever it means to be you in conscious awareness and then put that consciousness into a computer, a robot body, an organic body, a virtual reality, or some other realm? Can the consciousness be separated from the body?

There have been so many fun stories that have explored what this might be like.

In the film, Transcendence, starring Johnny Depp, the main character, a computer scientist, uploads his own consciousness into a quantum computer and then, through his own transcendence into something new, he frightens other people (who choose to fight him) as he tries to help all life on Earth transcend to a new state. The movie delves into themes like the ethical implications of digital immortality, the blurred lines between human and machine, and the dangers of unchecked technological advancement. It also leaves the audience to consider the question of whether the computer version of the main character was morally good, bad, or in between and if the transcendence he was offering is something we want or should fear.

In the Mass Effect series of video games, there are a variety of explorations of conscious experience, but the characters of the Geth and Reapers explore consciousness transfer and the idea of an amalgamated or harvested consciousness existing in machines. The Geth are not organic/biological beings that have had their consciousnesses transferred, but are instead networked bodies of an artificial intelligence that were created as tools by another race. However, they eventually become self-aware and fight for their own liberation, becoming enemies of most organic beings in the galaxy. But they are minimal threats compared to the larger threat of The Reapers—ancient machines made of countless species’ consciousnesses combined into massive powerful machines (that appear much like giant machine squids or even Cthulhu-inspired beings). The Reapers use the promise of technology in the galaxy to lure biological beings like ourselves into a trap that is sprung every 50,000 years, when the Reapers come back into the galaxy from far outside to “harvest” life—in turn, adding all of the consumed consciousnesses into their own structures (imagine being afloat in an ocean of conscious awareness where you have no agency to control what is happening to you or how you can respond to it).

There are many other examples in science fiction that explore these kinds of concepts. We see it in Neuromancer, Ghost in the Shell, Upload, The Matrix, in the Cylons in Battlestar Galactica, and in some episodes of Black Mirror, like "San Junipero" and "White Christmas" (both of which are tremendously thought provoking and worth a watch on their own even if you haven’t watched any other Black Mirror episodes).

Stories such as these are a great way for us to explore real concepts in science and philosophy about the nature of identity and authenticity, the role of the memory in the conceptualization of the self (would you be you without any of your memories?), the sheer nature of consciousness, and whether it may even be possible to disconnect what we experience as our conscious awareness—the self—from the physical construct that contains it—our bodies.

In some stories exploring these concepts we also see themes such as wealth inequality (who gets to be uploaded and what level of control would they have?), freedom vs. control (if you are uploaded into a virtual realm contained on a physical storage device, then who gets to control the device and what happens if the device is damaged or destroyed?), and even the question of the right to die vs. being forced into immortality (either as a punishment or simply unintentionally).

The latter is explored in a fun way in a short story by Paolo Bacigalupi called “Pocketful of Dharma”. Set in a futuristic (and very cyrberpunky) world where technology allows for the preservation of consciousness, the story follows Wang Jun—a beggar from the “hard life” in a future growing city in China—who inadvertently stumbles upon a data cube containing the consciousness of the Dalai Lama inside. As Wang Jun comes to understand the significance of what he's carrying (many people in the world around him want control of the data cube and the consciousness of the Dalai Lama), it becomes clear that the consciousness within the cube is trapped in a state of artificial immortality, unable to escape the endless existence imposed upon it. More so, the Dalai Lama wants to die and be released from the cube to continue his reincarnation cycle.

The story raises poignant questions about the right to die, as the Dalai Lama’s inability to find peace in death contrasts with the natural cycle of life and death that Wang Jun and the other impoverished characters experience. Bacigalupi uses this contrast to highlight the ethical dilemmas of extending life artificially and the potential suffering that comes from denying someone the ability to end their existence on their own terms. But the story also explores the question of what might happen to “you” (or what you think of as you) if you should be uploaded to a computer or storage device where someone has control over the actual physical container—just as we must question concepts of freedom for our bodies in our current existence as well.

There certainly are a lot of questions to be raised in this realm, with science fiction stories serving as a great way to explore some of the potential issues.

The first and foremost question for “consciousness uploading”, of course, is whether it’s even possible for a consciousness to exist outside of the body. We also have to consider whether taking a consciousness from a body and “uploading” it anywhere else will allow it to retain who/what it was before: would you still be you if you are uploaded—even if you have some of your own memories, this new version might not be experiencing consciousness anything close to the same way, and could be argued to not be the same “person” it was before. And then, of course, as some of the sci-fi stories I mentioned above have explored, we also have to wonder what the long term fate and impact of these new conscious “beings” would be.

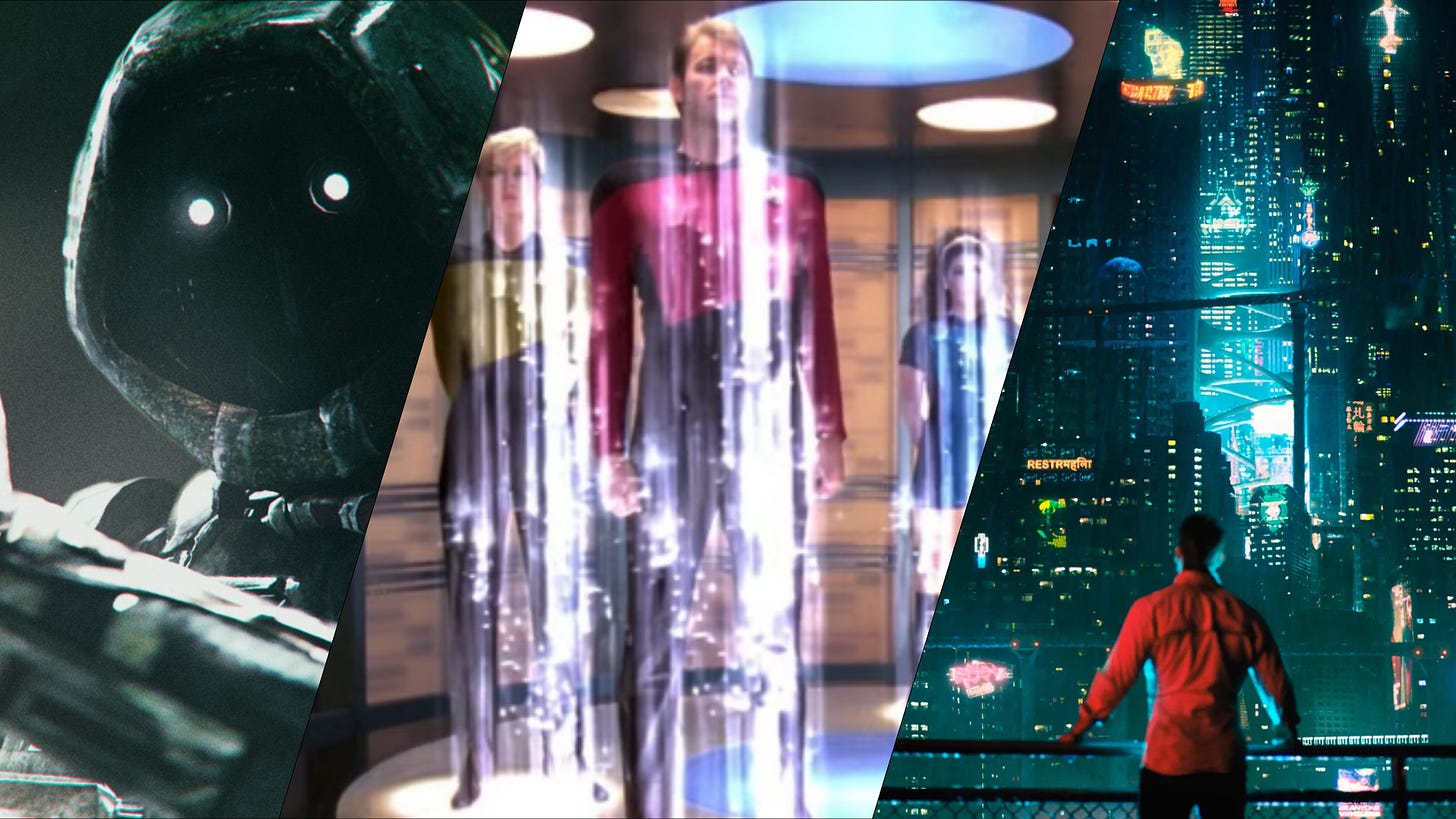

For the sake of my writing here, I want to explore a small subset of these concepts within story aspects from SOMA, from episodes of Star Trek, as well as in the series Altered Carbon (I don’t really believe in “spoilers”, but if you haven’t played SOMA, read/watched Altered Carbon, or, *gasp*, watched Star Trek at all, then you might want to get on that first).

SOMA: Which Simon is Which?

…And Which Version of You Would You Want to Be?

I’m happy to have stumbled upon SOMA. I’d asked ChatGPT to help me find some video game recommendations that might remind me of the themes and concepts from the Dead Space series (some of the best sci-fi horror I’ve ever experienced), and the AI did not disappoint.

SOMA explores the philosophical and psychological implications of consciousness, identity, and what it means to be human. The game is set in a dystopian future within an underwater research facility called PATHOS-II, where humanity’s survival is tied to technology after a global catastrophe (an impact from space—though you don’t ever learn all that much about the impact or the fallout on the surface).

The game begins with Simon Jarrett, an ordinary man in our modern day, who suffers a traumatic brain injury. To help treat his injury, his brain is scanned using a new, experimental technology. However, after undergoing the scan, Simon mysteriously awakens in the distant future (a century later), within the decaying PATHOS-II facility. He has no memory of how he got there, only to discover that his consciousness has been uploaded into an artificial body—a robot with a human mind.

Throughout the game, Simon learns that the original version of himself who had taken the brain scan had later died of his brain injury. But the scan itself had saved his consciousness and was used by the researcher to create a base level program for later work on separating human consciousnesses from their bodies. The player gets to wonder just how many digital copies of Simon’s consciousness were used and what level of awareness and agency each may have had.

In the dark and unsettling environment of PATHOS-II, the player interacting as this version of Simon has to explore what has happened to him in an environment where some of the few remaining people have been converted into monstrous forms by the AI system, WAU, which is also slowly taking over all of the systems of the deep ocean facility.

Along the way, Simon meets the consciousness of Catherine. She’s separated from her body and you only interact with her in a digital form stored on a device that you carry through the game. The player learns that Catherine had created a device called the ARK which would serve as a virtual environment for the remaining human consciousnesses to be stored in so that humans may experience some further existence. The ARK was supposed to have been launched into space, but Simon and Catherine learn that it hasn’t and that if they can get their own consciousnesses on the ARK they may be able to launch it into space and join others in the virtual environment for as long as the device persists.

There are two major times in the game where the question comes up of “which you would you want to be”?

At one point, Simon needs to transfer his consciousness into a new body to go deeper into the ocean. When he does so, he creates a split. The new version of him realizes that there is still an exact copy from that moment in time in the body he had just left. The player is given the choice of choosing to let this version live on or to kill it.

Finally, at the conclusion of the game, this kind of split comes again. One version of Simon is preserved in the way he had wanted, and one is left to realize that it is the remaining version (and may likely be trapped within a robot body with no real future except for a slow decay on the ocean floor).

SOMA’s narrative provides a haunting meditation on existential identity and the potential consequences of consciousness uploading.

Rather than offering easy answers, the game leaves players grappling with uncomfortable truths about what it means to persist beyond death, and whether living on as a copy can ever replace the original. It also leaves one wondering: “Which version of yourself would you choose to be if consciousness uploading left one version of you behind?”

Identity Crisis: The Transporter Problem in Star Trek

There’s a similar concept that comes up in the realm of Star Trek. While there have been so many great episodes that have asked questions about identity, self, autonomy, and consciousness, I think one of the most fun places where such concepts have been explored is in the technology of the transporter.

The transporter is a technology that routinely destroys an individual, breaking them apart into information and sending that information through space and time, and then rebuilds them somewhere else. It’s perfect for asking the question of whether you are still you after going through the process.

The ST:TNG episode "Second Chances" explores this “identity ambiguity” when a transporter accident creates two identical versions of the character William Riker—each with the same memories and personality at the time of the split—but both of whom have become very different over the intervening eight years before they meet again. The story challenges the idea of a singular, continuous self—if two versions of Riker exist, which one is the "real" him?

Of course, most fans of Star Trek will be aware of the ethical issues brought up in the ST:VOY episode “Tuvix”. In that story, a transporter malfunction causes the characters of Neelix and Tuvok to be merged into one new conscious being, Tuvix. This new person is its own conscious individual but also bears a mix of the memories and identity of the previous two people. The episode also then presents the moral question of whether it is justifiable to murder one new conscious being to resurrect two conscious beings who have died—raising rather difficult questions about whether continuity or uniqueness defines identity and how we value individuals (I personally am of the mindset that Janeway committed an immoral act in killing Tuvix to bring back her other two friends, but I’m always happy to consider other opinions there).

Transporter tech in Star Trek also touches on the psychological impact of being disassembled and reassembled—you really are killed for a period of time before being brought back to life.

In "Realm of Fear" (from ST:TNG), Lieutenant Barclay's phobia about transporters reflects an anxiety that his essence might be lost during the process. This episode also hints at a deeper fear: if the transporter does indeed create a new copy, does the original person die in every use? Much like the thought experiments of the Ship of Theseus or the Grandfather's Axe, where replacing some object one individual part at a time raises doubts about whether it remains the same object later, the transporter forces us to ask whether we are the sum of our memories or something more and whether we can be broken apart into information and then reassembled later as individuals (and, are we still individuals during the process of transporting?).

Ultimately, Star Trek offers no clear answers, leaving viewers to grapple with the unsettling possibilities. The transporter serves not just as a narrative device but as a tool for exploring the fragile nature of personal identity and the limits of technological progress. It challenges us to consider what truly makes us who we are—our physical continuity, our memories, or something deeper that can never be replicated. On top of that, it’s great for considering whether our consciousness could be removed from our bodies and built differently elsewhere.

Altered Carbon: Living Many Lives Across Many Bodies

Altered Carbon is a cyberpunk science-fiction series set in a future where human consciousness can be digitized and stored in devices called “stacks”, implanted near the base of the skull. These stacks allow people to transfer their consciousness into different bodies—called “sleeves”—making physical death largely irrelevant for those who can afford new bodies. While the series explores concepts of identity and consciousness, there are also questions about extreme wealth inequality and what a future would look like where some small number of individuals can amass so much wealth and power that they can do nearly anything they want. (I recently just finished a re-watch of the two-season series on Netflix, and realized it was a good time to pick up the three novels the show is based on. Will probably nerd out on those far more soon!)

The series follows Takeshi Kovacs, a former elite soldier and “Envoy,” who is revived centuries after his original body’s death to solve a high-profile murder. Throughout the story, Kovacs navigates a world where the wealthy, known as Meths, have achieved near-immortality by continuously transferring their minds into new sleeves. Meanwhile, others struggle with the psychological, ethical, and societal consequences of this technology. The series blends noir detective fiction with action and deep philosophical questions about identity, memory, and the soul in a world where bodies are disposable but consciousness is not.

The concept of “sleeving” or “re-sleeving” itself raises deep questions about identity, continuity, and what it means to be oneself.

One of the show’s central dilemmas is whether a person’s consciousness can remain truly continuous when transferred between bodies. If you wake up in a different body, as protagonist Takeshi Kovacs does, are you still the same person—or just a copy with the same memories? The ability to inhabit multiple sleeves throughout one’s lifetime challenges the notion that identity is tied to the body. It asks whether the self is purely informational—defined only by thoughts and experiences—or if the connection to a single, mortal body is fundamental to being “you.”

The series also explores the psychological toll of sleeving. Some characters struggle with body dysmorphia, trauma, and disorientation when placed into new sleeves, especially when those bodies don’t match their original identities. Others, like the ultra-rich “Meths,” who can transfer between bodies endlessly, face a different crisis—losing their sense of humanity altogether. This creates an existential tension: when someone can live forever by switching bodies, do they remain the same person, or does the absence of natural death erode what makes them human?

As philosopher Todd May (who was also an advisor for The Good Place) explores in his book “Death (The Art of Living)” it might be that having the potential for natural death—being mortal—is part of what brings our lives meaning (I personally don’t think that to be the case, but it is important to consider what an immortal existence, especially one where we have no consistent form, might mean for our very being).

Ultimately, Altered Carbon asks viewers to reconsider whether consciousness alone is enough to define the self.

If your memories and personality can be transferred to a new body, are you still you—or merely a simulation of who you once were? The series leaves us with unsettling questions about the nature of identity, suggesting that while technology may preserve consciousness, it might not fully replicate the essence of being human.

Philosophical Reflections & Projections on Existence

SOMA, Star Trek, and Altered Carbon are among many science fiction explorations of concepts related to identity, consciousness, and the self. I love these kinds of stories as they force us to explore some of our assumptions about what it means to be human, what it means to be ourselves, and what our futures may hold for the conscious experience of being (and I imagine those reading this far are probably just about as into sci-fi as me!).

Some of the best questions in these realms from sci-fi include:

If technology allows for the uploading or transfer of consciousness, is the result still "you"?

What happens to our sense of identity when it can exist across multiple versions, bodies, or realities?

Would you want to live on in a digital form, or would you prefer the continuity of your own, mortal body?

And, terrifyingly, what happens to our conscious experience if we are removed from our bodies but someone else has control over the fate of our existence?

At their core, these kinds of stories in SOMA, Star Trek, and Altered Carbon (and more) suggest that even if we master the science of consciousness uploading, we may not solve the deeper, philosophical question: What does it mean to be?

Ultimately, these stories remind us that technological progress will not erase the existential dilemmas we’ve grappled with for centuries.

Instead, they highlight how future advancements may amplify those questions. As we imagine a world where consciousness can be transferred or replicated, we must also ask ourselves: Which version of you would you want to be? Would you choose to live forever across bodies, or would you prefer the fleeting beauty of a life that is yours—and only yours—until its natural end?

In the end, these reflections are not just about technology or speculative futures.

These stories are about understanding who we are now. The choices we imagine making in these fictional worlds reflect the values we hold today—about life, death, freedom, and identity. And whether or not we ever reach the technological heights depicted in these stories, the question of what it means to be human will remain one of the most profound challenges we will face.